The Pokagon are opening the first tribal casino in Indiana, and they won't have to pay taxes. Kaitlin Lange/Indystar

When the Pokagon band of Potawatomi opened its Four Winds Casino Resort in Michigan in 2007, just 4 miles from the Indiana border, it immediately began siphoning business away from the nearby Blue Chip Casino Hotel Spa in Indiana.

In just one year, Michigan City's Blue Chip casino cut 165 employees and lost $58 million in revenue.

Now state officials and the casino industry as a whole are bracing for an even bigger hit. The Pokagon are poised to open Indiana's first Indian casino, in South Bend, in January.

Not only will it likely drain more business from nearby Blue Chip, but Indiana potentially stands to lose millions in casino tax revenue because tribal casinos are immune from such taxes.

► Trump: In Gary, memories of Donald Trump's casino promises

► Casinos: Plans for Terre Haute casino die in committee

► Politics: New Pence emails show archbishop asked him to intercede on behalf of killer Paula Cooper

That revenue stream is already under strain as the state's 11 existing casinos and two racinos face increasing competition from nearby gambling operations in neighboring states, particularly in the Cincinnati area.

In the past seven years alone, casino tax revenue to the state general fund has fallen by $237.4 million, or 35 percent.

Now the drop could be more precipitous.

"Nobody (in Indiana) has dealt with this before," said Ed Feigenbaum, editor of the Indiana Gaming Insight newsletter. "It's going to be a game changer, and it’s going to be particularly bad news for Blue Chip in Michigan City."

About the Pokagon casino

The new casino is a means of economic development for the Pokagon tribe's 5,000 citizens scattered throughout southern Michigan and northern Indiana.

The tribe had been separated until 1994 when it became federally recognized after decades of pushing to be reaffirmed. Since then, it has built homes for many of its citizens, a large casino in New Buffalo, Mich., and two other smaller satellite casinos in that state.

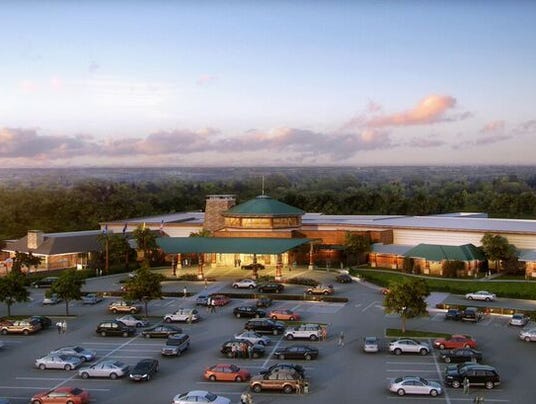

The 175,000-square-foot South Bend casino will be similar in size and appearance to the New Buffalo location. It will have 1,800 slot machines, restaurants, three bars, a coffee shop and retail outlets and employ 1,200 people.

Like the New Buffalo location, some of the decor and architecture is inspired by the tribe's history. The rotunda will feature the tribe's native basketry. A fire will be constantly burning in the rotunda, representing the ceremonial fires of the Potawatomi culture.

Tribe chairman John Warren said the casino revenue has had a tremendous impact on the Pokagons, providing the financial support necessary to return many to their ancestral homeland after being forced west by the U.S. government in the 1830s and allowing the tribe to provide health care and other services.

"It's because of the Pokagon band's tribal council and also advice and the wants and needs of our tribal citizens that we engaged in gaming," Warren said. "And it's just a success story from there. Most of the infrastructure and most of the services that were built in the last 10 years is because of Four Winds."

No other Native American tribe in Indiana has come close to being able to open a casino. To do so, the tribe must be federally recognized and then be approved for a land grant by the federal government.

"It's the first time in 200 years in Indiana that they actually have Indian country," Warren said. "And we're very proud of that."

In South Bend, the tribe is building its own police station as well as homes for six Pokagon families who want to move onto the 607-acre property. While that number is small compared to Native American reservations out west, leaders emphasized the potential for growth.

Nationally, tribes have opted to run casinos to improve conditions on reservations.

Since Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in 1988, tribal gaming has exploded. Indian gaming revenue reached a record $31.2 billion high in 2016. Twenty-eight states already have tribal gaming, according to the National Indian Gaming Commission.

While that's good news for Native Americans, it has put existing casinos and states reliant on casino revenue in a difficult position.

Uncharted territory for Indiana

Indiana is only beginning to learn how to navigate the uncharted territory.

State officials have hired an outside law firm to help make sense of the complex federal laws related to the tribe and its operations. Dykema Gossett, which has advised Wisconsin and Michigan on similar matters, will be paid $200,000 over the next year to assist the state.

The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act passed by Congress three decades ago gave tribal communities the ability to open casinos on their land without state approval or taxation, as long as they only offered Class II gaming. That essentially means most anything short of live table games and certain types of slot machines.

That doesn't mean, however, that tribes can't offer to provide revenue to local or state government.

The Pokagon have an agreement with South Bend to provide the city with $400,000 for water and sewer services, a maximum of $5 million toward community development over the next five years and 2 percent of the casino’s net win, or a minimum of $2 million, toward the city’s budget.

“The tribe was in their rights to go forward with gaming with or without us,” South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg said. “Our stance has always been that we are supportive, provided that this can be set up in a way that this is a net win for the community.”

The Pokagon also could negotiate with the state to win approval to offer live table games in exchange for sharing some revenue with state government, as they have in Michigan.

So far the tribe hasn’t pushed for an agreement and doesn't expect to do so in the near future, meaning the state is losing out on taxes essential to its general fund, economic development, the State Fair Commission and the Division of Mental Health.

A spokesman for Gov. Eric Holcomb said it would be "premature" to say whether he would sign a compact with the Pokagon to allow for table games or how much revenue he would expect in return.

Even if Holcomb decides to negotiate, his hands may be tied by the Indiana General Assembly. State lawmakers largely have been opposed to any sort of compact with tribes since the passage of the federal act.

When the Pokagon started to eye Indiana for a casino in 2015, the General Assembly passed a measure that requires lawmakers to approve any gambling compacts between tribes and the state.

Winning approval from the legislature could be challenging. Many lawmakers want to protect the interest of casinos in their own districts, and many others simply are opposed to expanding gambling beyond what the state already offers.

Earlier this year, a plan to create a state-licensed casino in Terre Haute died in committee before it could even make it to a floor vote.

“Any time you deal with gaming legislation, it’s always going to be challenging,” said Rep. Todd Huston, R-Fishers. “(Whether or not the compact is approved) is going to depend on what the details of the agreement are going to look like.”

If the state and the Pokagon came to an agreement, Indiana could salvage some of the tax dollars it would otherwise lose. The Pokagon paid Michigan $19.4 million and local governments $6.1 million for its New Buffalo and satellite casinos in 2016.

That’s still less than the $43 million on average that each of Indiana’s 11 casinos contributed to state and local taxes in fiscal year 2017.

But the tribe may not see any value in paying taxes or fees just to get table games. Frank Freedman, Four Winds’ chief operating officer, said expanding to live table games would not be that much of a win.

“In our industry, slots are overwhelmingly the larger percentage of our business. Overwhelmingly,” Freedman said. “So when you really start to sit down and look at the financial planning data, it was really easy for us to conclude that this is going to be a home run.”

A rendering of the inside of the Four Winds South Bend casino. (Photo: Provided by Four Winds Casino)

Casino towns fear future

Indiana's other casino towns, mostly on the fringes of the state, are bracing for the impact of even more competition.

Local governments collect taxes from both the casinos' admissions and wagering revenue, though that will change slightly under a new law. The state government also provides all communities, even those without casinos, some additional wagering tax revenue from casinos.

Many of the local communities have come to depend on casino revenue to pave streets, hire police officers, build fire stations and improve deteriorating water and sewer systems. But they've had to make considerable adjustments in recent years with the onslaught of competition in neighboring states and the looming prospect of even more tribal gaming.

When the first casinos started opening in Indiana in 1995, the state’s casinos had little if any out-of-state competition. Placed near state borders, the casinos were able to draw large portions of their customer bases from Indiana’s neighbors.

At the Hoosier gaming industry’s height, the amount of taxes casinos paid to Indiana was surpassed in only one other state — the gambling capital itself, Nevada.

But the addition of more tribal casinos in Michigan, video-game gambling in Illinois and the onset of legalized Ohio gambling all have chipped away at Indiana’s share of the market.

The three casinos in southeastern Indiana near Cincinnati are struggling to make even half of what they made prior to the onset of Ohio gaming.

Before Horseshoe Casino opened in Cincinnati in 2013, Hollywood Casino in Lawrenceburg was the second-highest grossing casino in Indiana; now it's the sixth. In fiscal year 2017, Hollywood brought in $169.8 million — 40 percent of the casino’s 2012 revenue.

The nearby Rising Star casino didn’t fare much better. It generated $51.8 million in revenue in 2017, compared to $92.6 million in 2012.

Rising Star’s parent company Full House Resorts is now investing $6 million in Rising Star in an effort to maintain its customer base.

“We believe our investments in the property will grow our revenues over time,” said Alex Stolyar, senior vice president of Full House Resorts. “However, we do not expect our revenues to ever return to the levels they were at prior to the introduction of gaming to Central Indiana and Ohio.”

Rising Star's tax money and grants have been used to hire more police officers in Rising Sun, purchase bulletproof vests for the sheriff’s department in Ripley County and install new sewer equipment in the city of Aurora.

“We’re talking about planting a massive infusion of economics into a smaller demographic, more rural, more income-challenged area,” said Rising Sun Mayor Brent Bascom. “It’s been a great relationship for our community.”

In recent years, though, the casino has had to cut the number of employees by 17.6 percent, or 127 people, and local taxes have fallen to $3.65 million during 2016 — just 62 percent of the local tax revenue generated in 2013.

Blue Chip Casino’s fate in northern Indiana could be similar to those in southeastern Indiana as it braces for the new tribal casino 40 minutes away.

Keith Smith, president and chief executive officer of Boyd Gaming, Blue Chip's owner, said he doesn't have any projections about the new competition's impact.

“We’ll be prepared to fight it out and see what happens,” Smith said in a quarterly call with shareholders. “We don’t have any predictions, but we’re certainly aware of it, certainly paying attention to it and certainly preparing for it.”

Michigan City, however, is already discussing what the competition will mean for the community. Its location along Lake Michigan offers a tourism industry apart from the casino, but city officials are still concerned.

In 2017, Michigan City brought in $10.8 million in casino taxes. In recent years, the city has used the money to build a $13 million police station, keep the police and fire fleet in good shape and contribute to technological needs of the school system.

Starting next year, though, city officials say they will have to adjust.

“It’s important to make sure that Blue Chip does thrive because their success does reflect on our community,” Michigan City Mayor Ron Meer said.

Buy Photo

Buy PhotoThe Four Winds casino is currently under construction and set to open in January 2018. (Photo: Kaitlin Lange/The Star)

More tribal casinos on the way?

The opening of Four Winds in South Bend could also rev up efforts for more tribal casinos in Indiana, escalating the competition.

In Michigan, tribal casinos already dominate the gaming industry. Eleven tribes own 23 casinos in a state where only three commercial casinos now exist.

Matt Bell, president of the commercial Casino Association of Indiana, knows what could lie ahead.

“We don’t believe this will be a one-time event,” he said. “We think that this is the beginning.”

Both the Miami Nation of Indians of the State of Indiana, located in Peru, and the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma have tried acquiring land for a casino.

The Miami Nation of Indians of the State of Indiana have been unable to obtain federal recognition as a tribe, the first step of being able to purchase tribal land. The Miami Tribe of Oklahoma is federally recognized but has yet to obtain the land it asked for in Indiana.

Feigenbaum doesn’t see President Donald Trump’s administration being any friendlier to tribes trying to gain federal recognition or casino land. In the '90s, Trump actively campaigned against the expansion of tribal gaming that threatened the revenue of his own casino.

Regardless of whether more tribal casinos join the scene, Bell says the industry in Indiana won't return to the revenue numbers it experienced at its height.

"When you think about Indiana gaming, when it was introduced 22 years ago, we were a monopoly in the Midwest," Bell said. "The competitive environment has changed dramatically."

Call IndyStar reporter Kaitlin Lange at (317) 432-9270. Follow her on Twitter: @kaitlin_lange.

Read or Share this story: http://indy.st/2xBlYi4

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|

Copyright © 2025 ToCasino.net Online Casino. All Rights Reserved. Designed by

Copyright © 2025 ToCasino.net Online Casino. All Rights Reserved. Designed by